Seventy years of alliances and cooperative peace since the end of World War II may give the impression that the wars that devastated Europe in preceding centuries are relegated to the past. History belies this assumption, however, with no guarantees that peace is permanent in Europe. The efforts by European states to build trust and integrate trade and defense in the post war years has created the basis for peace. This foundation is at risk as regional politics are increasingly characterized by apathy and distrust of institutions. Without preserving the framework of organizations, like the European Union (EU) and NATO, Europe runs the risk of returning to a time of chaos where violence and war are no longer conditions of the past.

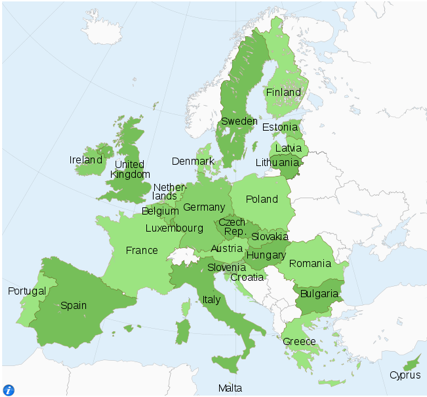

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the integrated Europe of today would have seemed inconceivable. Fatigue from half a century of war led leaders to create a framework that would keep countries from falling back into conflict. To that end, the European Coal and Steel Community was created in 1952. The idea was that if the two industries indispensable for war were tied together, it would make future war less likely among the members. Over the years more countries joined, and the organization expanded to include a customs union, eventually becoming the EU that we know today. The Schengen Agreement in 1985 ultimately led to the establishment of open borders between member countries and the free flow of people and goods from Finland to Portugal and Ireland to Cyprus. A common currency, while not adopted by all member countries, further connected the countries of Europe and its currently estimated 510 million residents.

As the economic foundations of the modern EU were being built, a similar effort was taking place in the field of security and defense. The perceived threat from the Soviet Union led to a mutual defense treaty between Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, and the United Kingdom in 1948. Later that year, the group added the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with the goal “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” A key provision of the organization is Article V, the agreement that an attack on one country is an attack on them all, cementing the security of the 29 member nations to one another. Despite cultural differences and often contentious histories, the countries of Europe painstakingly bound themselves to each other as time progressed. With the support and encouragement of other allies, particularly the United States, Europe endeavored to put the tragedy of centuries of war into the past.

There are now forces that aim to weaken or destroy these cooperative institutions. Brexit, or the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU, is a prime example of this destabilization. The increased popularity of far-right parties across the continent, many of whom advocate for isolationism, is another concerning trend. NATO has also faced criticism for having an outdated mission since the end of the Cold War and is now facing skepticism from the Trump administration over the utility of American participation in the Alliance. Provocations, including election meddling, from Russia and other adversaries add to concerns about the future of European stability.

Brexit: A Case Study

Of all the challenges facing Europe, Brexit is likely the most far-reaching. Voted on by the British people in a referendum in 2016, the U.K. is currently negotiating its departure from the EU’s single market allowing free movement of people and goods among its members. The U.K. is also considering leaving the EU customs union, which allows goods to cross international borders without being checked. The Leave campaign argued that leaving the EU would result in a more competitive economy, since the U.K. would be able to negotiate its own trade deals. Brexit-backers capitalized on frustration that bureaucrats in Brussels dictated British policy, from mundane issues such as the curvature of bananas to more existential topics like immigration. They also capitalized on anti-establishment sentiment that has risen in many Western democracies in recent years.

In practice, however, the negotiations between the U.K. government and the EU, and domestically among British politicians, have proven to be messy and inconclusive. Tension is growing within the U.K. as promises made by the Leave campaign – that the country will be able to renegotiate more favorable trade agreements, for example – have proven elusive. Parliament has also been unable to agree on a plan as the British government grapples with multiple unpopular options and no clear path forward for how to execute its departure without causing an economic catastrophe.

Brexit also has security implications for the EU, in particular at the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Northern Ireland is no stranger to violence. From the 1960s through the late 1990s, the region dealt with a conflict known as “The Troubles.” Irish nationalists and British unionists engaged in irregular warfare and terror attacks over the nationalists’ desire to unify Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland. During the thirty years of the conflict over 3,500 people died, more than half of whom were civilians.

The violence, for the most part, ended in 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement. The agreement resulted in the demilitarization of the combatant groups and a devolved government, which requires cross-community power sharing. The peace has generally held since the agreement went into place, though some of the more hardline groups denounced the agreement and have continued to agitate over the years. What all sides agree on, though, is that the free flow of people across the border has been a critical factor for keeping the peace. Where a physical barrier was once a symbol of a divided Ireland and a constant source of tension, the lack of demarcation between the two countries has eased the tensions considerably. Both countries being members of the EU and parties to the Schengen Agreement are directly responsible for the border remaining open.

The possible resurrection of border barriers has exacerbated lingering tensions in the region. In April 2019, riots began in the town of Derry after police carried out a number of searches due to concerns that militant republicans were storing firearms and explosives. Police were worried that, like last year, militants were preparing an attack to commemorate the 1916 rebellion in Dublin known as the Easter Rising. Tragically, a local journalist, Lyra McKee, was killed during the riot when republican militants fired shots towards the police vehicle that McKee was standing near. Several packages containing explosives were also found in March 2019 at the University of Glasgow and at three London transport hubs, including Heathrow Airport, further adding to concerns that the violence could escalate.

While authorities assess that the people behind both the riots and the explosive packages are less ideologically driven than the militant groups of the past, tensions remain high. Thirty years may have elapsed since the Good Friday Agreement, but sectarian discord has not disappeared. In many ways, the two sides have cemented their divisions, with more barriers or “peace walls” separating predominantly Nationalist and Unionist neighborhoods now than at the time the agreement was signed. An estimated 90 percent of Northern Irish schools continue to be segregated by religion. Peace has taken hold but remains fragile. The potential for events, like the murder of Lyra McKee, resulting in a reignition of violence is an ever-present concern.

While Brexit and the Northern Ireland border issue remain unresolved, it will continue to be a source for discord. However, there is some room for optimism. The one stabilizing benefit to Brexit is that the chaos it has created in the U.K. appears to have dampened enthusiasm elsewhere in Europe for additional EU exits. Eurosceptic parties now advocate for changes within the EU rather than full departures. Populists and far-right parties that previously advocated for leaving the EU or the common currency are now campaigning for decentralized decision-making or hardline immigration reforms. Nevertheless, the radical right is expected to do well in upcoming European parliament elections at the end of May and far right parties are represented in most parliaments across the EU. Whether they remain content with advocating for change within the confines of the EU or work to further dismantle Europe’s cooperative institutions in the years to come is unclear.

Brexit on its own is unlikely to directly cause the destruction of European institutions like the EU and NATO. But it does lead to weaker ties across the continent. Where once the U.K. was a steadfast partner to the other countries of Europe on all manner of issues, they are now engaged in divorce proceedings over economic terms. Nicola Sturgeon, the Minister of Scotland, has declared that Brexit should trigger a Scottish independence referendum by 2021. If successful, such a move could inspire other semi-autonomous regions of Europe, like the Catalonia or Basque regions in Spain, who have similar aspirations. If violence erupts again in Northern Ireland, conflict could spill over into the Republic of Ireland, further destabilizing the region. Russia, which has shown a willingness to exacerbate existing tensions could use these divisions to sow further discord on the European continent. It remains to be seen what other long-term effects may come of Brexit and how destabilizing they will be.

At the funeral of murdered Northern Ireland journalist Lyra McKee on April 24, Father Martin Magill urged the grieving community to use the tragedy as a catalyst for change. “Many of us will be praying that Lyra’s death in its own way will not have been in vain and will contribute in some way to building peace here,” he said. “I dare to hope that Lyra’s murder on HolyThursday night can be the doorway to a new beginning.” It is a message that perhaps all of Europe could benefit to hear, as so many of the institutions that Europe has taken for granted in recent decades struggle to survive apathy, attacks from isolationists, and foreign intervention. With luck it will not take further bloodshed, in Northern Ireland or elsewhere, to remind Europeans that peace, and the institutions that peace is built on, are worth preserving.